The Muqaddimah was written in 1377 by the Arab scholar and historian, Ibn Khaldun (1332 – 1406). It is the first in a series of books which make up the Kitab al-‘Ibar (the “Book of Lessons”), an ambitious work which provides an early account of the history of the world. The Muqaddimah – which serves as an introduction to the Kitab – sets out Ibn Khaldun’s philosophy of history. It is a truly astonishing piece of work which has earned him considerable posthumous acclaim. It outlines a number of important concepts and theories that were taken up and developed, centuries later, by Western scholars accredited with founding the discipline of sociology. In recognition of his early contribution to sociological thought, some modern thinkers have labelled Ibn Khaldun a “founding father” of the discipline.

The Islamic Golden Age

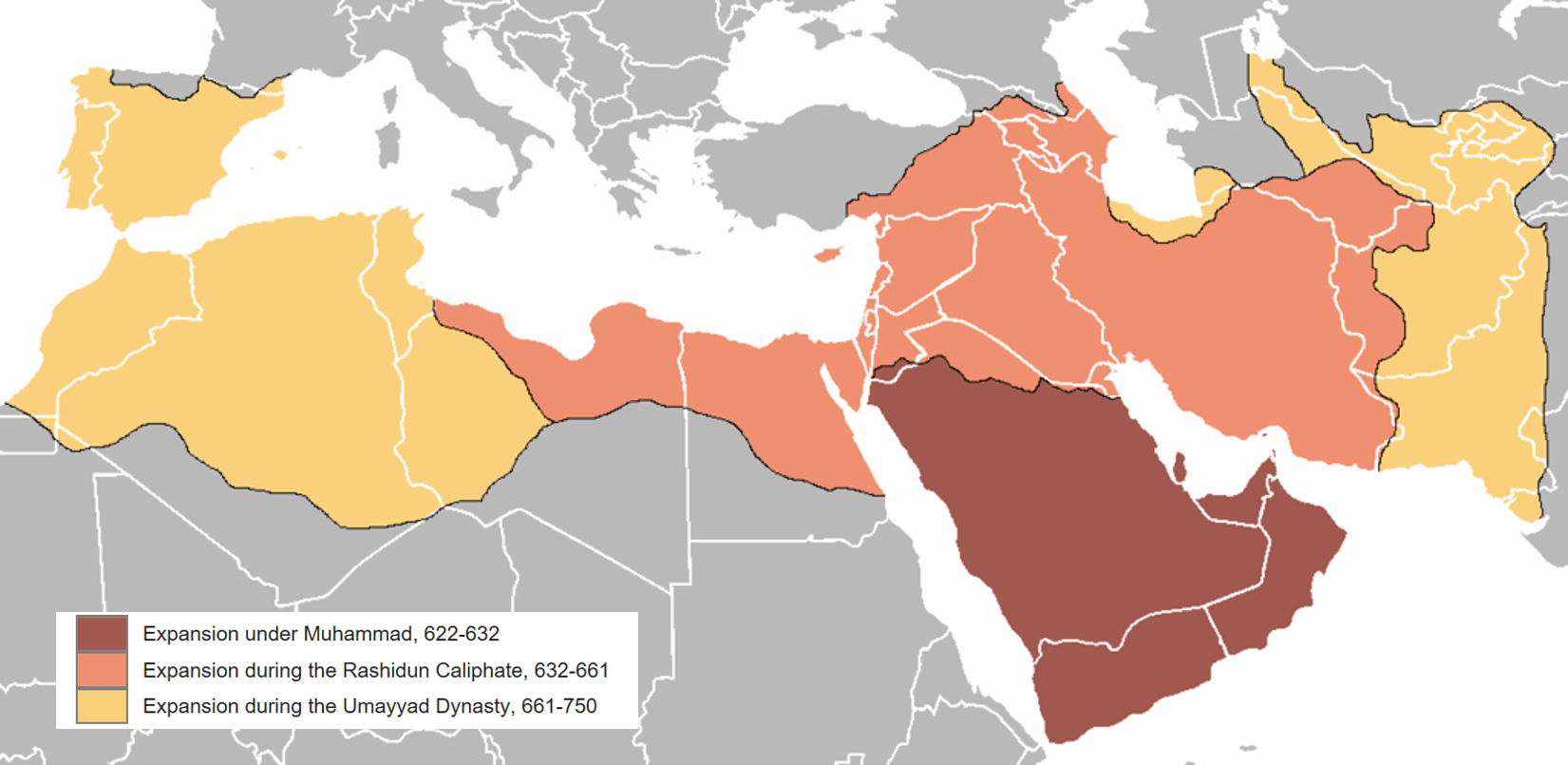

To fully appreciate the ideas contained within the Muqaddimah, one must first know a little about the historical context in which it was written. Ibn Khaldun was alive towards the end of “the Islamic Golden Age”; a period of history spanning the 7th to the 14th centuries which saw the establishment of an Islamic caliphate encompassing territories across the Middle East, North Africa and Southern Spain.

At the peak of its power, this Islamic empire was an unrivalled centre of economic and cultural activity, its major cities – Baghdad, Cairo and Cordoba – attracting merchants and scholars from around the globe. But by the 13th and 14th centuries the empire had entered a devastating spiral of decline. Baghdad – its capital city – had been sacked by a Mongol invasion in 1258, and Christians in Europe were conquering more and more territory in Moorish Spain, a dynamic which eventually led to the fall of the Iberian Peninsula in 1491.

It was against this turbulent backdrop that Ibn Khaldun – a proud Arab Muslim whose family had played a prominent role in the leadership of Muslim Spain – wrote the Muqaddimah. In many ways, the book can be interpreted as his explanation for why this great, triumphant Muslim empire of his descendants had disintegrated into feuding and decay. But what Ibn Khaldun achieved in the Muqaddimah was something far more remarkable; a general theory of history that could explain the rise and fall of all the great civilisations of the past.

The Role of “Assabiyah” in the Rise and Fall of Civilisations

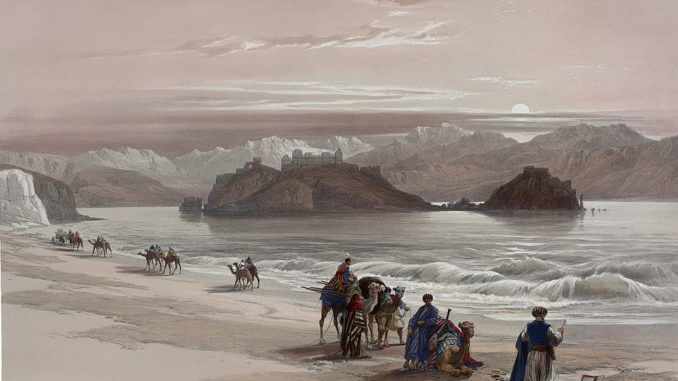

Ibn Khaldun’s analysis was grounded in his observations of the Bedouin tribes of the North African desert – a nomadic people whose way of life had remained largely unchanged over the centuries, and who he regarded as similar to the early founders of the Arabic Empire. While watching the Bedouins’ daily struggle to survive in the harsh and unforgiving desert, Ibn Khaldun arrived at an important conclusion: that co-operation was fundamental to human survival. Without the help of others, he noted, people could not effectively defend themselves from predatory animals, or obtain and cultivate enough food for their subsistence. This need for mutual help and support, he argued, was what ultimately led to the formation of tribal societies, which in turn, provided the foundations for more complex, urban civilisations.

Central to his explanation of how these societies evolved over time was an Arabic concept called “assabiyah”. This can loosely be translated to mean “group feeling” or “social solidarity” and refers to the bonds that exist between members of a social group. As Ibn Khaldun explained, “assabiyah” is something which tends to occur naturally amongst blood relatives; we have an instinctive concern for our families’ well-being that compels us to intervene if they are in danger or are being treated unjustly. This protective urge can, however, extend out towards other non-blood relatives who we come into close contact with, in particular those who provide us with mutual support in order to survive. In this sense, “assabiyah”, or “social solidarity”, can exist at the level of a family, but it can also develop amongst the wider tribe, or even a large society or empire.

“Assabiyah” can loosely be translated to mean “group feeling” or “social solidarity” and refers to the bonds that exist between members of a social group.

To Ibn Khaldun, “assabiyah” was the key to understanding why some tribes flourished and grew into larger, more complex societies and why others failed or broke down altogether. When a tribe’s social bonds were strong, he argued, they were more likely to be successful at defending themselves from external threats, pressing claims against rival tribes, and overcoming internal conflicts and rivalries. Tribes with weak “assabiyah” on the other hand would not be able to do any of these things effectively. In an evolutionary process, which seemed to anticipate Darwin’s notion of “survival of the fittest”, Ibn Khaldun described how the tribes with the strongest sense of solidarity would eventually rise to power by taking over other, weaker tribes whose inferior social bonds left them vulnerable to attack or internal breakdown. Over time, this evolutionary process would result in the creation of larger, more complex societies and, indeed, in some cases, great civilisations and empires.

Interestingly, Ibn Khaldun argued that this evolutionary dynamic was greatly intensified when a tribe developed a common religious ideology. This is because the unifying power of a shared religion significantly strengthened a group’s “assabiyah” turning them into an almost unstoppable force. He pointed to the development of the Islamic empire as an illustrative example of this; a civilisation which originated with the nomadic tribes of the Arabian desert whose swift conquest of vast swathes of territory was inspired by their desire to spread the religious teachings of the Prophet Muhammad.

While the most successful tribes and societies rose to power on the basis of their “assabiyah”, Ibn Khaldun noted this was also the key to understanding their eventual downfall. As he saw it, the rise and fall of civilisations was comparable to the life stages of an individual: it involved their birth, maturity, and death. The birth began with the tribal societies which were courageous and used to hardship. They had the strongest sense of “assabiyah” because their survival was completely dependent on their solidarity as a group. As these tribal societies rose to prominence, however, they eventually matured and aspired to a sedentary culture, leading to the development of more complex, urban societies and civilisations. These tended to be wealthier and more prosperous than the tribal societies that came before them, but over time their people became lazy and complacent, forgetting the qualities that led them to prominence in the first place.

While the most successful tribes and societies rose to power on the basis of their “assabiyah”, Ibn Khaldun noted this was also the key to understanding their eventual downfall.

Parallels with Today

It is astounding that over 600 years later, the concepts that Ibn Khaldun introduced in the Muqaddimah are still relevant to understanding the world today. Indeed, many governments now actively measure the extent of “social solidarity” or “social cohesion” present in their societies as an indicator of their overall health (see for example the EU’s Report on Economic, Social and Territorial Cohesion linked below). For it is generally accepted that nations built upon strong internal bonds – whose citizens share a common sense of identity and who feel able to trust their neighbours, their institutions and governments – are more likely to thrive and prosper than those which are internally divided and susceptible to fragmentation or breakdown.

With this in mind, the political polarisation that is sweeping across Western democracies today is a particularly worrying trend. The Brexit vote and the election of Donald Trump has exposed some deep-running divisions in the UK and the US, and the European project is threatened by the rise of more extreme political parties in a number of its member states. If Ibn Khaldun’s theory of history holds true, we might be witnessing the first stages in the decline of the Western powers that have dominated the world stage since the fall of the Islamic empire. Indeed, many commentators have argued that the 21st century will be known as the “Asian Century”; an era in which the fast-growing economies of China and India become the dominant world forces. The challenge laid down by Ibn Khaldun’s theory is whether these younger, more vigorous economies will have the strength of “assabiyah” required to maintain their rise to power and establish a new world order.

Further Resources

The eminent British historian, Arnold J. Toynbee, once described the Muqaddimah as “the greatest work of its kind that has ever been created by any mind in any time or place . . . the most comprehensive and illuminating analysis of how human affairs work that has been made anywhere.” It is indeed an extraordinary book that will be a joy to read for anyone with an interest in sociology or history .

If you would like to learn more about Ibn Khaldun and the Muqaddimah we would recommend listening to the BBC radio programme In Our Time which discusses Ibn Khaldun’s life and work. To complement your reading of the Muqaddimah , we would also recommend The Silk Roads – A New History of the World by Peter Frankopan which provides a contemporary analysis of the forces that have driven the rise and fall of empires, and places the Islamic Golden Age in its broader historical context.

You can also find further video resources on this topic at our Mind Attic YouTube channel playlist