Our journey through the history of Western political and social thought begins in the 5th century BC on a peninsula and archipelago of islands in South Eastern Europe – the region we broadly refer to today as Greece.

At this point in time, the Greek world looked very different. Rather than a unified nation state, the region consisted of a large number of independent city-states (known as poleis) each with their own armies, laws and systems of government. Some of these city-states were very small (we would barely recognise them as towns today), but others such as Athens, Sparta and Corinth were relatively large, with populations in the tens and even hundreds of thousands.

Most of the Greek city-states were ruled by a king-like figure or a small group of wealthy aristocrats. However, in Athens, political reforms had resulted in the establishment of a limited form of democracy – a term which comes from the Greek word demokratia meaning “rule by the people”. Under Athenian democracy, government decisions were taken by a public assembly in which all adult male citizens were eligible to participate. This assembly would meet frequently and debate and vote on proposals covering a range of topics, from taxation and public finance to matters of war and peace.

This political environment created the conditions for a Greek “Golden Age” – a flourishing of cultural and intellectual activity that was to last for two centuries. Playwrights, artists, historians and philosophers flocked to Athens from all over the Mediterranean to debate ideas and discuss the fundamental questions of life: What is “justice”? What is the “good life”? What is an “ideal city-state”?

It is against this historical backdrop that we consider our first group of thinkers – the Sophists – in our second post in this series. They were professional teachers, and masters in the art of public speaking, who prepared young men in the Greek city-states for the challenges of political life. Next, in our third post, we discuss the Greek Historians, Herodotus and Thucydides, who gave birth to the study of history by inquiring into the facts and causes of two great conflicts that shaped the Greek world: the Greco-Persian wars (480 – 479 BC) and the Peloponnesian War (431 – 404 BC). And in our fourth post of this series, we consider the Great Philosophers Socrates, Plato and Aristotle whose ideas laid the foundations for Western philosophical thought. It is no exaggeration to suggest that almost all contemporary philosophical debate can be traced back to the questions first raised and discussed by these three men over two millennia ago.

The End of the “Greek Golden Age” and the Rise of Alexander the Great

This extraordinary period of Greek intellectual and cultural development was not, however, destined to last. By the middle of the 5th century BC, relations between the two most powerful Greek city-states – Athens and Sparta – had become increasingly strained, a dynamic which led to the Peloponnesian War, an exhausting and bloody conflict which started in 431 BC and lasted almost 28 years. The war ended in total defeat for Athens – an outcome that was disastrous for the Greek region as a whole. For it created a power vacuum that Sparta was unable to fill, leaving the Greek region less stable and more vulnerable to outside forces.

Almost half a century later, in 359 BC, Philip II ascended the throne in Macedon – a territory to the north of the Greek peninsula. Under Philip’s leadership, the Macedonian army was transformed into a formidable military force which Philip used, together with his skills of diplomacy, to make himself the new master of Greece. After defeating the city-states of Athens and Thebes in the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC, Philip planned to use the combined might of the Greek and Macedonian armies to expand his empire into West Asia and North Africa. However, his untimely death in 336 BC left his son, Alexander, to fulfil this aim in his stead.

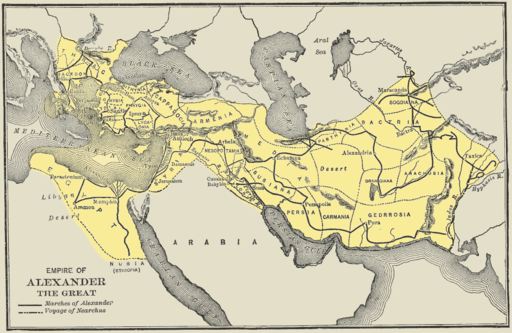

Alexander went on to establish one of the world’s largest empires stretching from Greece to north-western India, an achievement which has since earned him the title “Alexander the Great”. The period from the beginning of Alexander’s reign up until the Roman conquest of the eastern Mediterranean is often referred to as the “Hellenistic Age” – an era in which Greek culture and language spread across the east, as far as the borders of India.

Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Kings that followed him were absolute monarchs. Under their rule, the Greek city-states were effectively transformed into administrative centres within a larger empire; they no longer had complete autonomy over their own laws, finances or armies. With less power to shape their own political environments, Greek philosophers turned their focus away from the outer world of politics towards the inner life of men.

Three important schools of thought emerged during this era – Epicureanism, Stoicism and Scepticism. These philosophies – which are discussed in posts five, six and seven of this series – focused on matters such as the pursuit of happiness, how to cope with pain and suffering, and how to achieve mental tranquillity in the face of the troubling contradictions of the world. They gave comfort and hope to many at a time of great political and social upheaval.

The Decline of the Hellenistic Empire and the Rise of Rome

After Alexander’s death in 323 BC, the Hellenistic empire broke down into three competing kingdoms that continued to fight one another for territory and power. Over time, the incessant warfare weakened these kingdoms heavily, creating the opportunity for a new regional power to sweep in. This came in the shape of Rome – a small city-state in central Italy which had established itself as a Republic two centuries earlier, after its people had overthrown a tyrannical monarchy. After a series of military successes against its neighbouring rivals, Rome had become the dominant power in the Italian peninsula, and by the third century BC was challenging Carthage – the other major force in the Western Mediterranean – and the Hellenistic Kingdoms in the East.

Over the next two centuries, the Roman Republic grew from strength to strength, gradually conquering territory across Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. Greek communities came under Roman rule on a piecemeal basis, and as they did, the city of Rome became flooded with Greek ideas, art and literature. Philosophical ideas that had originated in Athens were soon being discussed all over the Roman world. A form of Stoicism was adopted as the main philosophical school of the Romans, but Epicureanism was also very popular amongst the upper middle classes. Some Romans, however, preferred to draw upon and combine ideas from the various Greek schools of philosophical thought – a system of philosophy we now refer to as “eclecticism”. The most famous of the Roman Eclectics was Marcus Tullius Cicero whom we discuss in our eighth post of this series, a lawyer-politician who rose to the highest political office in Rome.

Cicero was a staunch defender of the Roman Republic. Like many other Romans, he believed that Rome’s success was built upon its mixed constitution – a form of government which combined elements of monarchy, aristocracy and democracy. The Roman consuls who were elected annually were its monarchs, the Roman Senate were its aristocracy, and the people of Rome were its democracy. According to Cicero it was the delicate system of checks and balances that existed between these three parts of the Roman government that kept the powers of individuals in check, and provided the stability upon which Rome’s military successes were forged.

The Decline of the Roman Empire

Cicero’s beloved Roman Republic was not, however, built to last. The demands of defending, policing and extending a large overseas empire stretched the Roman constitution to its limits, and the Roman people ended up giving more and more power to individual military commanders. In 48 BC the military general, Julius Caesar seized control of the city and installed himself as dictator, effectively bringing the Republic to an end. After his assassination in 44 BC by a group of senators, a long period of civil war ensued, and in 27 BC Caesar’s great-nephew and appointed heir, Augustus established himself as the first emperor of Rome.

Under Augustus and his successors, Rome continued to expand its territory. But from the late 2nd century AD onwards, plagues, natural disasters, famines and invasions by “barbarian” tribes gradually brought the empire to its knees. In 285 AD the empire was divided into an eastern and western region which were governed separately. Gradually, Rome lost its place as the capital of the empire and power shifted eastwards to the new capital of Byzantium (modern day Istanbul). During the 5th century AD, continued invasions from Germanic tribes caused the Western Empire to steadily disintegrate before finally falling in 476 AD.

The fall of the Roman Empire in the west marked the end of the classical era and ushered in a new phase of Western history, where political and social thought was heavily influenced by Christianity. This new era, often referred to as “The Middle Ages”, forms the subject of the next instalment – Part II of our Lifetime Reading Plan.

Further Resources

To learn more about this fascinating historical period we would highly recommend reading the following books:

The Ancient Greeks by M.I. Finley. This provides an excellent introduction to Ancient Greek history, starting with the Mycenaean civilisation of 1400-1200 BC and taking us up to the time of Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age. The main focus of Finley’s book is on the Classical Age – the time period spanning the fourth and fifth centuries BC – in which some of the greatest cultural achievements took place in all of Greek history. In describing this amazing period of intellectual development, Finley takes us through innovations in Greek literature, science, philosophy, architecture, sculpture and painting.

The Hellenistic World by F.W. Walbank examines the political events during the Hellenistic Age – from the time of Alexander the Great’s death until the Roman conquest of the eastern Mediterranean. This was a time where Greek culture and language spread east, as far as the borders of India. Walbank expertly describes the different social systems of the peoples that came under Greek rule, and discusses the important developments in literature, science and technology during this period.

SPQR by Mary Beard is a fascinating read that captures the rise of Rome from an insignificant village in central Italy to a global superpower. The book is entitled SPQR because this is the abbreviation that the Romans used for their state. It stands for “Senatus PopulusQue Romanus” which means “the Senate and People of Rome”. In this book, Mary Beard provides compelling answers to key questions such as: How and why did the Empire happen? Why did Rome acquire an empire? And why did it fall? The book has also been complemented by a fascinating BBC documentary – Empire Without Limit – which is now available to buy on DVD. We highly recommend both the book and the DVD.

Further video resources are also available on our Mind Attic YouTube channel playlist.