In his bestselling book, What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets, the political philosopher Michael Sandel articulates a concern that will resonate with many people living in Western societies today: the increasing dominance of markets – and market values – in our everyday lives. Since the end of the Cold War, Sandel argues that Western societies such as the US and the UK have become complacent about the role and reach of markets, allowing them to creep into all aspects of our social lives. In his words: “we have drifted from having a market economy towards being a market society.”1 This distinction could be characterised as follows:

- In a market economy, the market is an economic tool for organising productive activity; it is an adjunct to society;

- In a market society, the market controls, regulates and directs all aspects of human behaviour: our thoughts, attitudes and social relationships.

Sandel provides a variety of examples to illustrate this shift in our society and behavioural norms. These demonstrate how the logic of buying and selling has become all pervasive, seeping into areas of life that were previously held outside the realm of markets. For example, he points out that, amongst other things, individuals or companies are now able to buy: access to higher education and decent healthcare; the right to pollute; the right to advertise within – or acquire “naming rights” for – public spaces such as sports stadia and public parks; access to reproductive technologies that can provide us with “designer” babies or the services of surrogate mothers that can carry our children; and greater political influence through the financing of election campaigns. Furthermore our public services – our hospitals, schools, public policing, defence and security – have become increasingly hostage to the logic of the market, either through privatisation or through the use of financial incentives.

So why does this matter? Sandel posits two major reasons for us to be concerned:

- The issue of growing inequality in society; and

- The corruption of our moral values and attitudes towards certain goods and activities.

In relation to the former, he explains that in a market society, where more and more things can be bought and sold, citizens with low incomes will inevitably suffer:

“As money comes to buy more and more – political influence, good medical care, a home in a safe neighbourhood rather than a crime-ridden one, access to elite schools rather than failing ones – the distribution of income and wealth looms larger and larger. Where all good things are bought and sold, having money makes all the difference in the world. This explains why the last few decades have been especially hard on poor and middle-class families. Not only has the gap between rich and poor widened, the commodification of everything has sharpened the sting of inequality by making money matter more.” 2

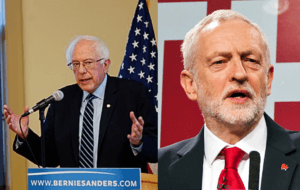

Indeed the issue of inequality has attracted growing political attention in recent times, with research highlighting the wide gap between the richest and poorest citizens of many Western capitalist societies. This economic context has provided the catalyst for the rise of left-wing politicians, such as Jeremy Corbyn and Bernie Sanders, who have run for office on a platform of reversing market reforms or bringing the market back under the control of the state.

The second reason for Sandel’s discomfort is more nuanced and is to do with our capacity to deal with the social problems we face. This is because, he argues, our shift towards a market society has led to a change in our thinking and a corruption in our attitudes and moral values. For while economists tend to see markets as neutral, in that they do not pass any judgement on the nature of the good or service that is being bought or sold, Sandel argues that the opposite is true:

“….markets don’t only allocate goods; they also express and promote certain attitudes toward the goods being exchanged.” 3

Again, he provides a range of examples to illustrate his point but one of particular significance relates to the issue of climate change and the need for global co-operation to reduce overall carbon emissions. As Sandel explains, some economists have advocated a market-based approach to this problem involving the creation of tradeable pollution permits. Within such a scheme, countries would be able to meet their global obligations by either reducing their own carbon emissions or paying another country to reduce theirs. In other words, countries would be given the option to buy and sell the right to pollute. The economic argument for such an approach is that this will promote economic efficiency because developed countries will have the option of funding cheaper projects in developing countries that will ultimately lead to the same net result of reducing carbon emissions overall. What Sandel is concerned about, however, is the impact such a market-oriented approach might have on our attitudes towards our environment:

“Letting rich countries buy their way out of meaningful changes in their own wasteful habits reinforces a bad attitude – that nature is a dumping ground for those who can afford it. Economists often assume that solving global warming is simply a matter of designing the right incentive structures and getting countries to sign on. But this misses a crucial point: norms matter. Global action on climate change may require that we find our way to a new environmental ethic, a new set of attitudes toward the natural world we share. Whatever its efficiency, a global market in the right to pollute may make it harder to cultivate the habits of restraint and shared sacrifice that a responsible environmental ethic requires.” 4

What this example shows is that by restricting our thoughts, values and behaviours to the logic of the market we may be reducing our capacity to think differently about how to deal with important social problems. Sandel’s book prompts us to think more broadly about these issues from an ethical, moral and even spiritual standpoint. His desire is to bring about a wider debate in society about the role and reach of markets, so we can better decide where they do and don’t belong.

Further Resources

What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets is a highly readable book full of fascinating, and at times, rather worrying examples of where the logic of the market has come to dominate public debate on a range of important issues. In tackling this subject, Sandel poses a number of interesting and challenging questions to the reader: Should we financially reward children for good marks? Is it ethical to pay people to donate organs? What about hiring mercenaries to fight our wars? Should we outsource inmates to for-profit prisons? And should citizenship be for sale?

As well as being an excellent writer, Sandel has gained a large following for his hugely popular lectures at Harvard University. We have included a number of these, as well as some of his other public lectures, on our Mind Attic YouTube channel playlist. We highly recommend you view these as a great example of a lecturer at the top of his game.

Sandel has also written many other interesting articles for magazines and newsletters, some of which touch upon the themes raised in this post. A selection of these are as follows:

- It’s Immoral to Buy the Right to Pollute – New York Times

- What Isn’t For Sale? – The Atlantic

-

Market Reasoning as Moral Reasoning: Why Economists Should Re-engage with Political Philosophy,The Journal of Economic Perspectives

- Right-wing populism is rising as progressive politics fails – is it too late to save democracy? in the New Statesman

You can also find more information on Sandel’s work on justice, ethics, democracy and markets at his Harvard website.