For a long time, the Greeks’ interest in the past was largely concerned with mythical stories – tales of events involving supernatural beings or Gods – that were passed down from generation to generation in oral form. The Iliad and The Odyssey, written around the 8th century BC by the Greek poet Homer, are the first and most famous written examples of this oral tradition. They recount the events surrounding the Trojan war, and are replete with tales of war heroes and the activities of the Olympian Gods.

While the Homeric poems may have contained some kernels of truth, they did not represent a factual account of the past. It was not until the 5th century BC that a more systematic form of historical inquiry began to take shape. This was largely due to the work of two Greek thinkers – Herodotus and Thucydides – who set out to critically investigate two major events that shaped the Greek world: the Greco-Persian wars (480 – 479 BC) and the Peloponnesian War (431 – 404 BC). By making a serious attempt to inquire into the facts and causes of these two great conflicts, Herodotus and Thucydides gave birth to the study of history as we know it today.

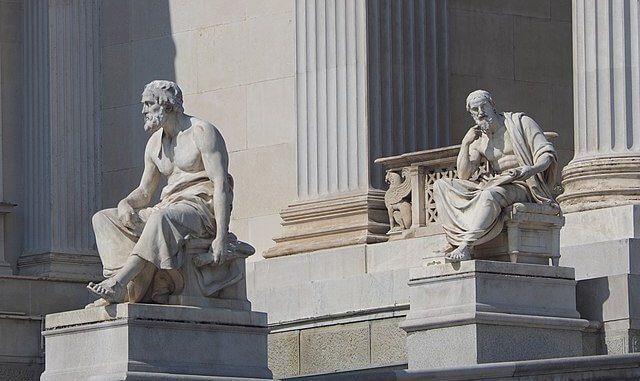

Herodotus (c. 484 – c. 425 BC) is often considered “the Father of History” for writing the first systematic study of the past. His magnum opus, The Histories, gives an historical account of the Greco-Persian Wars (480 – 479 BC) in which a coalition of Greek city-states achieved victory against the great military power at the time: the Persian Empire. As the war had taken place before Herodotus’ lifetime, he tried to reconstruct events by drawing on the oral reports of survivors and younger men who could recall the stories of their elders. On this, he said “my duty is to report the things reported….it is not to believe them all alike”. While his methods fell short of modern historians, Herodotus’ determination to interrogate the facts and causes of the war – and his shift in focus away from the Gods towards the human world of politics – marked the beginnings of a new form of critical investigation into the past.

Thucydides (c. 460 – c. 400 BC) followed in Herodotus’ footsteps with his analysis of the causes and conduct of The Peloponnesian War (431 – 404 BC) – a great conflict between the leading Greek city-states, Athens and Sparta, which took place during his lifetime. Like Herodotus, Thucydides’ objective was not only to give a reliable account of the war, but also to explain why it happened and to pinpoint the factors that led to the Athenian empire’s eventual defeat. He did so with less romance and more precision than Herodotus, focusing narrowly on the facts and providing rational, objective explanations of events. Moreover, the Gods were excluded entirely from his analysis; he chose instead to focus his attention on the psychologies, motives and behaviours of the people who led Athens, Sparta and their allies. His search for the truth, and his rational, matter-of-fact style greatly influenced historical writers in the centuries that followed, and his work continues to inspire political thinkers today.